My teacher wants to see me after class.

I don’t know why. I have absolutely no idea. I’m twelve years old, and I’m not a troublemaker of any sort. I’m far too shy for that.

She scratches her nose, as if she’s uncomfortable. It’s hot in the classroom, and I’m uncomfortable too.

“Your results came back from the English exam.”

I remember that we took an exam a few days ago, an international one. It’s supposed to test our ability in English. All the students speak English-we’re an English-medium school in a former British colony- but we have wildly varying levels of proficiency.

She says, as if it were a problem rather than an achievement, “You have a Distinction.”

I look at the certificate she hands me. It says my name right there, on top of a scoring key. I see that Distinction is the highest score.

“You’re the only student in the class that got Distinction. But don’t think this makes you special.”

I am lost, but she continues: “I’ve seen your attitude in class –you’re very arrogant. As arrogant as the devil. I don’t want this to encourage you. You have to learn some humility. You’re not that good.”

There’s a few more words, but I don’t hear them. Finally she dismisses me, and I can sense that she is relieved. I walk out of the room clutching my Distinction certificate in small hot hands. Now I know it doesn’t mean anything.

*

Where to begin.

We obsess over beginnings. People want a good origin story. They ask this question all the time, when did it begin? They ask this of gay people, of sick people, and of artists. When did you find out? When did it begin? And for me the answer is always “When did what begin? If you mean, when did I start writing, well, I started writing when I was seven years old.”

It’s true. I knew I wanted to write from the time I could write. I stole my parents’ office notebooks and wrote poems in them. I still remember lines from one poem: “The lacy little wavelet/On the brown shore.” I remember being inordinately proud of that line.

That’s when I started writing, but I never called myself a writer. I was just good at English, that’s all. Writing was something I did for myself. I did it all through high school, and then college, and then law school. I kept journals; I blogged; I tweeted; I wrote jokes on Facebook because I had to write. I dreamed of growing up to be a real writer. I was like Wendy in Peter Pan: not ready to face the heartbreak of being grown up.

It’s an interesting question: this question of who gets to call themselves a writer, a real writer. Is it a good or bad thing? Why do white twenty-year girls on Thought Catalog declare with swagger “I’m working on my first book about New York”, when Haruki Murakami says that being a writer is a kind of embarrassing thing? What mysterious world divides those two?

Some say you’re a real writer when you get paid for writing. Most people would agree that you can call yourself a writer when you’ve been published. I blew past both those milestones and still didn’t call myself a writer. Like Murakami, I disliked the very word. When people said of me, she writes, I said, “I’m a lawyer.” I didn’t want to seem foolish. Writers were people like John Steinbeck and Ernest Hemingway: meaty, Big, important. Writers were not alright at writing. Writers were people who were very, very, very good.

For a while, I was obsessed with talent shows. There’s this talent show called The Voice. It’s a pretty cheesy show, to be honest. Hopeful people come from all over America, from New York and Massachusetts and small towns in the Midwest, people with real careers already, grown- ups. They walk on to a stage –the judges are sitting with their backs to the contestants, so they have no idea what they look like. Then the spotlight comes up, and they begin to sing.

If a judge likes their voice, they hit a button that turns their chair around. That moment, when the chair turns around, is the main reason I watch the show. That expression on the face of the contestant — rich, complicated, joy struggling with disbelief — is one we are rarely allowed to witness.

For the people on The Voice, it’s a moment of vindication. Somebody, Somebody Who Mattered, had told them that they were a real singer.

Artists often talk about that moment. It’s a dream: to be “discovered” the same way a talent scout may see a sulky, skinny 14 year old in the mall and realize she has the face of a supermodel. To be a young Roald Dahl sending a famous writer notes for his story and to get the reply “You’ve written my story already. Did you know you were a writer?”

Of course, it rarely happens that way. It’s more likely to happen like it happened to J.K. Rowling, who struggled through rejections from so many publishers before one took on Harry Potter.

*

Step Two: Being good with rejection.

It’s deep winter in Massachusetts, and all around me the sky is gray. I’m sitting in my college advisor’s office, and he’s telling me that he’ll look at my work.

“I’m going to tell you the truth,” he warns, twinkling at me from behind his desk. “Some people don’t want to hear the truth. But I’ll tell it to you. I can’t lie about your writing. I know when something’s not good.”

I am amused. “Have you ever been wrong?”

“Like, for instance, Sylvia Plath’s Daddy is not a good poem.”

“Really? Sylvia Plath’s Daddy? Really?”

“Answer me this: what’s it about? What do all those extravagant words mean? That mess of stark images?”

I thought quickly. “Well, it’s about her troubled relationship with her father, who she sees as a kind of Nazi figure in her life, right?”

“Yeah, but what does it mean to say The black telephone’s off at the root? What, exactly, does that mean?”

I’m confused. “I think it means that he can’t influence her anymore.”

“You think, but you’re not sure. Which is why it’s not a great poem.”

I don’t want to challenge him. I don’t yet have the entitlement to challenge people on their opinions. It will take me many more years, many long and painful years, to learn the first rudiments of it.

“So? Will you show me your work?”

With a smile, I decline. I hurry out of his office.

If this man, this confident white man in his office knows that Sylvia Plath is not a great poet, what would he make of me? I cannot imagine.

*

There’s a lot of talk about hard work, too.

The problem with hard work is that it’s fundamentally boring to talk about. When Biggie raps “Birthdays was the worst days/Now we sip champagne when we’re thirsty,” we’re enraptured by his vision, by the romance of it, of going from nothing to something. It has to feel like a dream to us: it can’t feel like someone laying brick patiently over brick and announcing one day Here is my house. Which is, sadly, how these things happen.

It’s true that there is no substitute for talent. But talent without hard work is nothing, nothing at all. It flares briefly and explodes in the grey world, and afterwards we are not sure if it was anything at all.

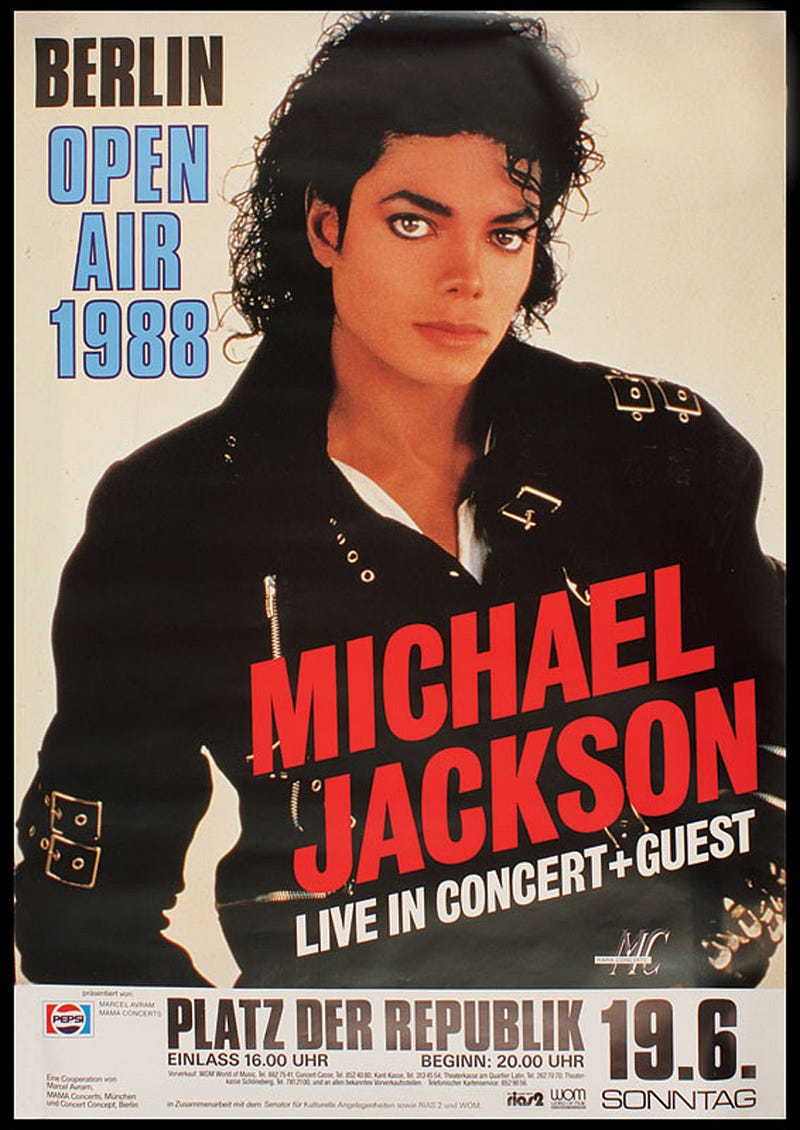

I remember interviewing a woman who had worked with Michael Jackson, a musician, and I remember her telling me how hard he worked.

“He’s the hardest working man I ever met in my life,” she said. “My whole life long. He was in the studio before other people and he was there long after other people left.”

I wondered why he had to work that hard if he was Michael Jackson. It didn’t occur to me that he had to work that hard because he was Michael Jackson.

*

It is nearly summer.

I am sitting in front of yet another teacher. This one is a guidance counselor at my boarding school.

We are playing the old, old, game of “Guess What Will Happen to Everybody When They Grow Up.”

Some kids get doctors, some get engineers, and some get lingerie designers. (My teacher likes to get creative.)

It’s my turn. She looks at me speculatively, and says “This one will be a housewife. She’ll have two kids by the time she’s twenty-five.”

I know she doesn’t mean it unkindly. In fact, she thinks it’s a compliment. I’m so shy, so painfully awkward in my adolescence, that she sees nothing special in me. She imagines my dreams to be narrow, circumscribed by my circumstances.

Her words are burning in me, red and large like flowers. I will never forget them, I tell myself. I never do.

*

There is a point to all these stories, I promise. I’m getting to it.

If you have the genuine disease — if you are an honest-to-goodness dreamer — you have to understand a few things. The life is filled with people saying No to you. If you’re a woman, if you’re brown, many more people will say No to you. Many people will not believe that you’re special. They will tell you that you’re not special. Unless you have the kind of entitlement that comes with being rich, white, and having supportive parents, you will believe them. You will not have the audacity to move to New York at twenty to work on your first book. You would not dare.

It will come slow to you, agonizingly slow. (There’s a phrase in India for people like this: strugglers. Strugglers are people who want to become famous actors. It’s the most appropriate word to describe their lives.)

You will not quit your job right away. Maybe you will never be lucky enough to quit. Maybe you will have to work nights and weekends and lunch breaks, with no sexy Hollywood montage to speed things up.

Hardest of all to hear, most painful, is this: maybe the moment will never come. Strugglers are often doomed. Is that what you wanted to hear? It’s not, but what choice do you have?

You have to wake up every day, every single day, and build your sand castle with aching hands, with your aching raw hands. You have to own the shame and struggle of being an artist, and try not to listen when people laugh — because people will laugh. Worse: they will pity you, the way they pity people who link to their Soundcloud under Nicki Minaj videos.

Nobody ever believes it until you get your book deal, your record deal, your movie deal. You will be the only one that believes it right until it happens. What choice do you have?

In the end, I decided that you’re a writer when, in the words of Rainer Maria Rilke, you “would die if you were forbidden to write.” If you must write. That is the answer. Sweet, aching, satisfying and simultaneously heartbreaking as it is to hear, that is the only answer.